What Is a Litter of Baby Rabbits Called

| Rabbit Temporal range: Late Eocene–Holocene, | |

|---|---|

| |

| European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Lagomorpha |

| Family unit: |

|

| Genera | |

| |

Rabbits, too known every bit bunnies or bunny rabbits, are small mammals in the family Leporidae (which also contains the hares) of the order Lagomorpha (which besides contains the pikas). Oryctolagus cuniculus includes the European rabbit species and its descendants, the world'due south 305 breeds[i] of domestic rabbit. Sylvilagus includes xiii wild rabbit species, amid them the 7 types of cottontail. The European rabbit, which has been introduced on every continent except Antarctica, is familiar throughout the world as a wild prey beast and as a domesticated class of livestock and pet. With its widespread effect on ecologies and cultures, the rabbit is, in many areas of the world, a office of daily life—every bit food, article of clothing, a companion, and a source of artistic inspiration.

Although once considered rodents, lagomorphs like rabbits accept been discovered to have diverged separately and earlier than their rodent cousins and have a number of traits rodents lack, like 2 extra incisors.

Terminology and etymology

Male rabbits are called bucks; females are called does. An older term for an developed rabbit used until the 18th century is coney (derived ultimately from the Latin cuniculus ), while rabbit once referred only to the immature animals.[2] Another term for a young rabbit is bunny, though this term is often applied informally (peculiarly by children) to rabbits generally, especially domestic ones. More recently, the term kit or kitten has been used to refer to a young rabbit.

A group of rabbits is known every bit a colony or nest (or, occasionally, a warren, though this more than commonly refers to where the rabbits live).[iii] A group of babe rabbits produced from a single mating is referred to as a litter [4] and a group of domestic rabbits living together is sometimes chosen a herd.[five]

The word rabbit itself derives from the Middle English rabet , a borrowing from the Walloon robète , which was a diminutive of the French or Middle Dutch robbe .[6]

Taxonomy

Rabbits and hares were formerly classified in the order Rodentia (rodent) until 1912, when they were moved into a new order, Lagomorpha (which also includes pikas). Below are some of the genera and species of the rabbit.

-

Brachylagus idahoensis

Pygmy rabbit

-

Nesolagus netscheri

Sumatran Striped Rabbit

(Model)

-

Oryctolagus cuniculus

European rabbit

(Feral Tasmanian specimen)

-

Pentalagus furnessi

Amami rabbit

(Taxidermy specimen)

-

Romerolagus diazi

Volcano rabbit

(Taxidermy specimen)

-

Sylvilagus aquaticus

Swamp rabbit

(Juvenile)

-

Sylvilagus audubonii

Desert cottontail

-

Sylvilagus bachmani

Brush rabbit

-

Sylvilagus brasiliensis

Tapeti

(Taxidermy specimen)

-

Sylvilagus palustris hefneri

Lower Keys marsh rabbit

- Gild Lagomorpha

- Family Leporidae (in part)

- Genus Brachylagus

- Pygmy rabbit, Brachylagus idahoensis

- Genus Bunolagus

- Bushman rabbit, Bunolagus monticularis

- Genus Lepus [a]

- Genus Nesolagus

- Sumatran striped rabbit, Nesolagus netscheri

- Annamite striped rabbit, Nesolagus timminsi

- Genus Oryctolagus

- European rabbit, Oryctolagus cuniculus

- Genus Pentalagus

- Amami rabbit/Ryūkyū rabbit, Pentalagus furnessi

- Genus Poelagus

- Central African Rabbit, Poelagus marjorita

- Genus Romerolagus

- Volcano rabbit, Romerolagus diazi

- Genus Sylvilagus

- Swamp rabbit, Sylvilagus aquaticus

- Desert cottontail, Sylvilagus audubonii

- Brush rabbit, Sylvilagus bachmani

- Forest rabbit, Sylvilagus brasiliensis

- Mexican cottontail, Sylvilagus cunicularis

- Dice'southward cottontail, Sylvilagus dicei

- Eastern cottontail, Sylvilagus floridanus

- Tres Marias rabbit, Sylvilagus graysoni

- Omilteme cottontail, Sylvilagus insonus

- San Jose brush rabbit, Sylvilagus mansuetus

- Mountain cottontail, Sylvilagus nuttallii

- Marsh rabbit, Sylvilagus palustris

- New England cottontail, Sylvilagus transitionalis

Hare

Johann Daniel Meyer (1748)

Rabbit

Johann Daniel Meyer (1748)

Differences from hares

The term "rabbit" is typically used for all Leporidae species excluding the genus Lepus. Members of that genus are instead known as hares or jackrabbits.

Lepus species are typically precocial, built-in relatively mature and mobile with pilus and good vision, while other rabbit species are altricial, built-in hairless and blind, and requiring closer intendance. Hares live a relatively lone life in a simple nest above the ground, while most other rabbits live in social groups in burrows or warrens. Hares are generally larger than other rabbits, with ears that are more than elongated, and with hind legs that are larger and longer. Descendants of the European rabbit are normally bred equally livestock and kept as pets, whereas no hares take been domesticated - the breed called the Belgian hare is a domestic rabbit which has been selectively bred to resemble a hare.

Domestication

Rabbits have long been domesticated. Beginning in the Center Ages, the European rabbit has been widely kept as livestock, starting in ancient Rome. Selective breeding has generated a wide multifariousness of rabbit breeds, of which many (since the early on 19th century) are too kept equally pets. Some strains of rabbit take been bred specifically equally enquiry subjects.

As livestock, rabbits are bred for their meat and fur. The earliest breeds were important sources of meat, and and then became larger than wild rabbits, but domestic rabbits in modern times range in size from dwarf to giant. Rabbit fur, prized for its softness, tin be institute in a wide range of coat colors and patterns, also as lengths. The Angora rabbit breed, for example, was developed for its long, silky fur, which is often paw-spun into yarn. Other domestic rabbit breeds have been developed primarily for the commercial fur trade, including the King, which has a short plush coat.

Biological science

Development

Development of the rabbit heart

(wax models)

Considering the rabbit's epiglottis is engaged over the soft palate except when swallowing, the rabbit is an obligate nasal breather. Rabbits have two sets of incisor teeth, one behind the other. This way they can be distinguished from rodents, with which they are often dislocated.[7] Carl Linnaeus originally grouped rabbits and rodents under the class Glires; later, they were separated equally the scientific consensus is that many of their similarities were a result of convergent evolution. However, recent DNA analysis and the discovery of a common ancestor has supported the view that they do share a common lineage, and thus rabbits and rodents are now often referred to together as members of the superorder Glires.[8]

Morphology

Since speed and agility are a rabbit'south main defenses confronting predators (including the swift fox), rabbits take large hind leg bones and well developed musculature. Though plantigrade at rest, rabbits are on their toes while running, bold a more than digitigrade posture. Rabbits utilise their stiff claws for digging and (along with their teeth) for defence force.[9] Each front pes has four toes plus a dewclaw. Each hind pes has 4 toes (but no dewclaw).[10]

Melanistic coloring

Oryctologus cuniculusEuropean rabbit (wild)

Most wild rabbits (especially compared to hares) have relatively total, egg-shaped bodies. The soft coat of the wild rabbit is agouti in coloration (or, rarely, melanistic), which aids in camouflage. The tail of the rabbit (with the exception of the cottontail species) is night on top and white beneath. Cottontails take white on the top of their tails.[11]

As a outcome of the position of the eyes in its skull, the rabbit has a field of vision that encompasses nigh 360 degrees, with just a small blind spot at the span of the nose.[12]

Hind limb elements

This epitome comes from a specimen in the Pacific Lutheran University natural history collection. It displays all of the skeletal articulations of rabbit's hind limbs.

The anatomy of rabbits' hind limbs are structurally similar to that of other land mammals and contribute to their specialized form of locomotion. The bones of the hind limbs consist of long basic (the femur, tibia, fibula, and phalanges) besides as brusk bones (the tarsals). These bones are created through endochondral ossification during development. Like most state mammals, the round head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum of the ox coxae. The femur articulates with the tibia, but not the fibula, which is fused to the tibia. The tibia and fibula articulate with the tarsals of the foot, normally called the human foot. The hind limbs of the rabbit are longer than the front end limbs. This allows them to produce their hopping course of locomotion. Longer hind limbs are more capable of producing faster speeds. Hares, which take longer legs than cottontail rabbits, are able to move considerably faster.[thirteen] Rabbits stay just on their toes when moving; this is called Digitigrade locomotion. The hind feet take iv long toes that let for this and are webbed to forbid them from spreading when hopping.[fourteen] Rabbits do non accept hand pads on their feet like most other animals that employ digitigrade locomotion. Instead, they have coarse compressed hair that offers protection.[15]

Musculature

The rabbits hind limb (lateral view) includes muscles involved in the quadriceps and hamstrings.

Rabbits have muscled hind legs that allow for maximum force, maneuverability, and acceleration that is divided into 3 main parts; foot, thigh, and leg. The hind limbs of a rabbit are an exaggerated feature. They are much longer than the forelimbs, providing more force. Rabbits run on their toes to proceeds the optimal stride during locomotion. The force put out past the hind limbs is contributed to both the structural anatomy of the fusion tibia and fibula, and muscular features.[16] Os formation and removal, from a cellular standpoint, is directly correlated to hind limb muscles. Action force per unit area from muscles creates force that is then distributed through the skeletal structures. Rabbits that generate less force, putting less stress on bones are more decumbent to osteoporosis due to os rarefaction.[17] In rabbits, the more than fibers in a muscle, the more than resistant to fatigue. For example, hares have a greater resistance to fatigue than cottontails. The muscles of rabbit's hind limbs can be classified into four principal categories: hamstrings, quadriceps, dorsiflexors, or plantar flexors. The quadriceps muscles are in charge of strength production when jumping. Complementing these muscles are the hamstrings, which aid in short bursts of action. These muscles play off of one another in the aforementioned mode equally the plantar flexors and dorsiflexors, contributing to the generation and actions associated with forcefulness.[xviii]

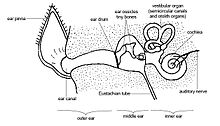

Ears

A Kingdom of the netherlands Lop resting with 1 ear up and one ear down. Some rabbits tin arrange their ears to hear afar sounds.

Within the gild lagomorphs, the ears are utilized to notice and avoid predators. In the family Leporidae, the ears are typically longer than they are broad. For example, in black tailed jack rabbits, their long ears encompass a greater surface area relative to their body size that allow them to detect predators from far away. Assorted to cotton tailed rabbits, their ears are smaller and shorter, requiring predators to be closer to detect them earlier they tin can flee. Evolution has favored rabbits having shorter ears and so the larger expanse does non cause them to lose heat in more than temperate regions. The reverse tin be seen in rabbits that live in hotter climates, mainly because they possess longer ears that accept a larger surface area that assist with dispersion of rut also as the theory that sound does non travel well in more arid air, opposed to cooler air. Therefore, longer ears are meant to aid the organism in detecting predators sooner rather than later in warmer temperatures.[19] [ page needed ] The rabbit is characterized past its shorter ears while hares are characterized past their longer ears.[20] [ page needed ] Rabbits' ears are an of import construction to aid thermoregulation and find predators due to how the outer, center, and inner ear muscles coordinate with one another. The ear muscles also assistance in maintaining balance and move when fleeing predators.[21]

Outer ear

The auricle, also known as the pinna, is a rabbit's outer ear.[22] The rabbit's pinnae stand for a fair part of the body surface area. Information technology is theorized that the ears aid in dispersion of estrus at temperatures above 30 °C with rabbits in warmer climates having longer pinnae due to this. Another theory is that the ears office as shock absorbers that could assist and stabilize rabbit's vision when fleeing predators, simply this has typically only been seen in hares.[23] [ page needed ] The rest of the outer ear has aptitude canals that lead to the eardrum or tympanic membrane.[24]

Center ear

The middle ear is filled with three basic called ossicles and is separated by the outer eardrum in the back of the rabbit'southward skull. The three ossicles are chosen hammer, anvil, and stirrup and act to subtract audio before information technology hits the inner ear. In general, the ossicles act as a bulwark to the inner ear for audio energy.[24]

Inner ear

Inner ear fluid chosen endolymph receives the sound energy. Subsequently receiving the energy, afterward inside the inner ear at that place are two parts: the cochlea that utilizes sound waves from the ossicles and the vestibular apparatus that manages the rabbit'south position in regards to movement. Inside the cochlea there is a basilar membrane that contains sensory pilus structures utilized to ship nerve signals to the brain and then it can recognize different sound frequencies. Inside the vestibular apparatus the rabbit possesses three semicircular canals to aid discover athwart motion.[24]

Thermoregulation

Thermoregulation is the process that an organism utilizes to maintain an optimal torso temperature independent of external weather.[25] This process is carried out by the pinnae, which takes up most of the rabbit's body surface and incorporate a vascular network and arteriovenous shunts.[26] In a rabbit, the optimal trunk temperature is around 38.5–40℃.[27] If their body temperature exceeds or does not run into this optimal temperature, the rabbit must return to homeostasis. Homeostasis of body temperature is maintained by the apply of their large, highly vascularized ears that are able to change the amount of blood flow that passes through the ears.

Rabbits use their big vascularized ears, which aid in thermoregulation, to go along their body temperature at an optimal level.

Constriction and dilation of blood vessels in the ears are used to command the core body temperature of a rabbit. If the core temperature exceeds its optimal temperature greatly, blood period is constricted to limit the amount of blood going through the vessels. With this constriction, there is only a limited corporeality of blood that is passing through the ears where ambient oestrus would be able to heat the blood that is flowing through the ears and therefore, increasing the body temperature. Constriction is also used when the ambient temperature is much lower than that of the rabbit's core torso temperature. When the ears are constricted information technology again limits blood flow through the ears to conserve the optimal body temperature of the rabbit. If the ambient temperature is either fifteen degrees above or below the optimal body temperature, the claret vessels will dilate. With the blood vessels being enlarged, the blood is able to pass through the large surface expanse, causing it to either rut or absurd down.

During hot summers, the rabbit has the capability to stretch its pinnae, which allows for greater surface area and increment heat dissipation. In common cold winters, the rabbit does the opposite and folds its ears in order to subtract its expanse to the ambience air, which would decrease their body temperature.

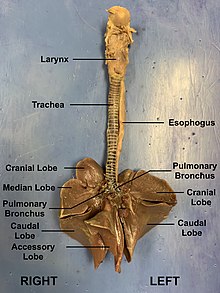

Ventral view of dissected rabbit lungs with cardinal structures labeled.

The jackrabbit has the largest ears within the Oryctolagus cuniculus group. Their ears contribute to 17% of their total trunk surface area. Their large pinna were evolved to maintain homeostasis while in the farthermost temperatures of the desert.

Respiratory system

The rabbit's nasal crenel lies dorsal to the oral crenel, and the 2 compartments are separated past the hard and soft palate.[28] The nasal cavity itself is separated into a left and right side by a cartilage barrier, and information technology is covered in fine hairs that trap dust earlier it can enter the respiratory tract.[28] [29] [ folio needed ] As the rabbit breathes, air flows in through the nostrils along the alar folds. From there, the air moves into the nasal cavity, too known as the nasopharynx, down through the trachea, through the larynx, and into the lungs.[29] [ page needed ] [30] The larynx functions as the rabbit'due south phonation box, which enables it to produce a broad variety of sounds.[29] [ page needed ] The trachea is a long tube embedded with cartilaginous rings that prevent the tube from collapsing equally air moves in and out of the lungs. The trachea so splits into a left and correct bronchus, which meet the lungs at a structure called the hilum. From at that place, the bronchi split into progressively more than narrow and numerous branches. The bronchi branch into bronchioles, into respiratory bronchioles, and ultimately stop at the alveolar ducts. The branching that is typically found in rabbit lungs is a clear example of monopodial branching, in which smaller branches separate out laterally from a larger central branch.[31]

The structure of the rabbit's nasal and oral cavities, necessitates breathing through the olfactory organ. This is due to the fact that the epiglottis is fixed to the backmost portion of the soft palate.[30] Within the oral cavity, a layer of tissue sits over the opening of the glottis, which blocks airflow from the oral cavity to the trachea.[28] The epiglottis functions to prevent the rabbit from aspirating on its nutrient. Further, the presence of a soft and hard palate allow the rabbit to breathe through its nose while it feeds.[29] [ page needed ]

Monopodial branching as seen in dissected rabbit lungs.

Rabbits lungs are divided into four lobes: the cranial, center, caudal, and accessory lobes. The right lung is made up of all four lobes, while the left lung only has two: the cranial and caudal lobes.[31] In order to provide space for the centre, the left cranial lobe of the lungs is significantly smaller than that of the correct.[28] The diaphragm is a muscular structure that lies caudal to the lungs and contracts to facilitate respiration.[28] [30]

Digestion

Rabbits are herbivores that feed by grazing on grass and other leafy plants. In result, their nutrition contains large amounts of cellulose, which is hard to digest. Rabbits solve this trouble via a form of hindgut fermentation. They pass two distinct types of carrion: hard droppings and soft black glutinous pellets, the latter of which are known as caecotrophs or "nighttime droppings" [32] and are immediately eaten (a behaviour known every bit coprophagy). Rabbits reingest their own droppings (rather than chewing the cud as do cows and numerous other herbivores) to assimilate their nutrient further and excerpt sufficient nutrients.[33]

Rabbits graze heavily and rapidly for roughly the beginning half-60 minutes of a grazing period (normally in the late afternoon), followed by almost half an hour of more selective feeding.[ commendation needed ] In this time, the rabbit will also excrete many difficult fecal pellets, beingness waste matter pellets that will not exist reingested.[ citation needed ] If the environment is relatively not-threatening, the rabbit will remain outdoors for many hours, grazing at intervals.[ citation needed ] While out of the couch, the rabbit will occasionally reingest its soft, partially digested pellets; this is rarely observed, since the pellets are reingested equally they are produced.[ commendation needed ]

Video of a wild European rabbit with ears twitching and a jump

Hard pellets are fabricated up of hay-like fragments of establish cuticle and stalk, being the final waste product production after redigestion of soft pellets. These are but released outside the couch and are not reingested. Soft pellets are usually produced several hours after grazing, after the difficult pellets have all been excreted.[ citation needed ] They are made up of micro-organisms and undigested plant cell walls.[ citation needed ]

Rabbits are hindgut digesters. This means that most of their digestion takes place in their big intestine and cecum. In rabbits, the cecum is about x times bigger than the stomach and information technology forth with the large intestine makes up roughly 40% of the rabbit's digestive tract.[34] The unique musculature of the cecum allows the abdominal tract of the rabbit to separate gristly textile from more digestible material; the fibrous material is passed as feces, while the more nutritious cloth is encased in a mucous lining as a cecotrope. Cecotropes, sometimes called "night feces", are high in minerals, vitamins and proteins that are necessary to the rabbit's health. Rabbits eat these to encounter their nutritional requirements; the mucous blanket allows the nutrients to laissez passer through the acidic stomach for digestion in the intestines. This procedure allows rabbits to extract the necessary nutrients from their food.[35]

The chewed plant material collects in the large cecum, a secondary chamber between the large and small intestine containing large quantities of symbiotic leaner that help with the digestion of cellulose and as well produce certain B vitamins. The pellets are about 56% bacteria by dry weight, largely accounting for the pellets being 24.iv% protein on boilerplate. The soft feces form here and contain upward to five times the vitamins of hard feces. After being excreted, they are eaten whole past the rabbit and redigested in a special part of the stomach. The pellets remain intact for upwardly to six hours in the tummy; the bacteria inside go on to assimilate the plant carbohydrates. This double-digestion process enables rabbits to use nutrients that they may have missed during the first passage through the gut, too as the nutrients formed by the microbial activity and thus ensures that maximum diet is derived from the nutrient they eat.[xi] This process serves the same purpose in the rabbit as rumination does in cattle and sheep.[36]

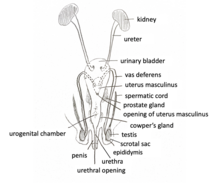

Dissected image of the male rabbit reproductive system with central structures labeled.

Because rabbits cannot vomit,[37] if buildup occurs within the intestines (due oft to a diet with insufficient fibre),[38] intestinal blockage can occur.[39]

Reproduction

Diagram of the male rabbit reproductive system with main components labeled.

The adult male person reproductive system forms the same as almost mammals with the seminiferous tubular compartment containing the Sertoli cells and an adluminal compartment that contains the Leydig cells.[40] The Leydig cells produce testosterone, which maintains libido[40] and creates secondary sex characteristics such equally the genital tubercle and penis. The Sertoli cells triggers the production of Anti-Müllerian duct hormone, which absorbs the Müllerian duct. In an developed male rabbit, the sheath of the penis is cylinder-like and can be extruded as early equally two months of age.[41] The scrotal sacs lay lateral to the penis and contain epididymal fat pads which protect the testes. Betwixt ten and 14 weeks, the testes descend and are able to retract into the pelvic cavity in order to thermoregulate.[41] Furthermore, the secondary sex activity characteristics, such equally the testes, are complex and secrete many compounds. These compounds includes fructose, citric acid, minerals, and a uniquely high corporeality of catalase.[40]

Diagram of the female rabbit reproductive system with master components labeled.

The adult female reproductive tract is bipartite, which prevents an embryo from translocating between uteri.[42] The ii uterine horns communicate to two cervixes and forms one vaginal culvert. Along with being bipartite, the female person rabbit does not go through an estrus cycle, which causes mating induced ovulation.[41]

The average female rabbit becomes sexually mature at three to 8 months of age and tin can conceive at whatsoever time of the twelvemonth for the duration of her life. Still, egg and sperm production tin can begin to decline after three years.[40] During mating, the male person rabbit will mount the female person rabbit from behind and insert his penis into the female and make rapid pelvic hip thrusts. The encounter lasts only 20–xl seconds and subsequently, the male will throw himself backwards off the female person.[43]

The rabbit gestation period is short and ranges from 28 to 36 days with an boilerplate period of 31 days. A longer gestation menses will generally yield a smaller litter while shorter gestation periods will requite birth to a larger litter. The size of a single litter can range from iv to 12 kits assuasive a female to deliver upwards to 60 new kits a year. Afterward nascency, the female can become pregnant again as early every bit the next day.[41]

The mortality rates of embryos are loftier in rabbits and tin be due to infection, trauma, poor nutrition and environmental stress and so a high fertility charge per unit is necessary to counter this.[41]

Sleep

Rabbits may announced to be crepuscular, but their natural inclination is toward nocturnal activity.[44] In 2011, the average sleep time of a rabbit in captivity was calculated at 8.4 hours per 24-hour interval.[45] Equally with other prey animals, rabbits frequently sleep with their eyes open, so that sudden movements will awaken the rabbit to answer to potential danger.[46]

Diseases

In addition to being at risk of disease from common pathogens such as Bordetella bronchiseptica and Escherichia coli, rabbits can contract the virulent, species-specific viruses RHD ("rabbit hemorrhagic disease", a form of calicivirus)[47] or myxomatosis. Among the parasites that infect rabbits are tapeworms (such as Taenia serialis), external parasites (including fleas and mites), coccidia species, and Toxoplasma gondii.[48] [49] Domesticated rabbits with a nutrition lacking in loftier fiber sources, such every bit hay and grass, are susceptible to potentially lethal gastrointestinal stasis.[l] Rabbits and hares are about never found to be infected with rabies and have non been known to transmit rabies to humans.[51]

Encephalitozoon cuniculi, an obligate intracellular parasite is also capable of infecting many mammals including rabbits.

Environmental

Rabbit kits one hour afterward birth

Rabbits are prey animals and are therefore constantly aware of their surround. For case, in Mediterranean Europe, rabbits are the main casualty of scarlet foxes, badgers, and Iberian lynxes.[52] If confronted past a potential threat, a rabbit may freeze and find then warn others in the warren with powerful thumps on the ground. Rabbits have a remarkably wide field of vision, and a skilful deal of information technology is devoted to overhead scanning.[53] They survive predation by burrowing, hopping abroad in a zig-zag motion, and, if captured, delivering powerful kicks with their hind legs. Their strong teeth let them to eat and to seize with teeth in gild to escape a struggle.[54] The longest-lived rabbit on record, a domesticated European rabbit living in Tasmania, died at historic period 18.[55] The lifespan of wild rabbits is much shorter; the boilerplate longevity of an eastern cottontail, for instance, is less than 1 year.[56]

Habitat and range

Rabbit habitats include meadows, woods, forests, grasslands, deserts and wetlands.[57] Rabbits live in groups, and the all-time known species, the European rabbit, lives in burrows, or rabbit holes. A group of burrows is called a warren.[57]

More than than half the world's rabbit population resides in North America.[57] They are also native to southwestern Europe, Southeast Asia, Sumatra, some islands of Japan, and in parts of Africa and South America. They are non naturally found in nearly of Eurasia, where a number of species of hares are present. Rabbits first entered South America relatively recently, equally part of the Slap-up American Interchange. Much of the continent has just one species of rabbit, the tapeti, while most of Due south America's southern cone is without rabbits.

The European rabbit has been introduced to many places around the world.[11]

Rabbits take been launched into space orbit.[58]

Environmental problems

Impact of rabbit-proof fence, Cobar, New South Wales, 1905

Rabbits take been a source of ecology problems when introduced into the wild past humans. As a effect of their appetites, and the rate at which they breed, feral rabbit depredation tin be problematic for agriculture. Gassing (fumigation of warrens),[59] barriers (fences), shooting, snaring, and ferreting have been used to command rabbit populations, but the most effective measures are diseases such as myxomatosis (myxo or mixi, colloquially) and calicivirus. In Europe, where rabbits are farmed on a large scale, they are protected against myxomatosis and calicivirus with a genetically modified virus. The virus was developed in Espana, and is benign to rabbit farmers. If it were to make its fashion into wild populations in areas such equally Australia, it could create a population nail, as those diseases are the most serious threats to rabbit survival. Rabbits in Australia and New Zealand are considered to be such a pest that state owners are legally obliged to control them.[threescore] [61]

As food and wearable

Saint Jerome in the Desert

[Note rabbit being chased by a domesticated hound]

Taddeo Crivelli (Italian, died about 1479)

Rabbit being prepared in the kitchen

Simulation of daily life, mid-15th century

Hospices de Beaune, France

In some areas, wild rabbits and hares are hunted for their meat, a lean source of loftier quality poly peptide.[62] In the wild, such hunting is achieved with the aid of trained falcons, ferrets, or dogs, every bit well equally with snares or other traps, and rifles. A caught rabbit may be dispatched with a sharp blow to the back of its head, a practice from which the term rabbit punch is derived.

Wild leporids contain a small portion of global rabbit-meat consumption. Domesticated descendants of the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) that are bred and kept as livestock (a practice called cuniculture) account for the estimated 200 million tons of rabbit meat produced annually.[63] Approximately ane.2 billion rabbits are slaughtered each year for meat worldwide.[64] In 1994, the countries with the highest consumption per capita of rabbit meat were Malta with eight.89 kg (xix lb 10 oz), Italy with v.71 kg (12 lb 9 oz), and Cyprus with 4.37 kg (nine lb 10 oz), falling to 0.03 kg (1 oz) in Japan. The figure for the United States was 0.14 kg (5 oz) per capita. The largest producers of rabbit meat in 1994 were Prc, Russia, Italian republic, French republic, and Spain.[65] Rabbit meat was once a mutual article in Sydney, Australia, only declined later on the myxomatosis virus was intentionally introduced to command the exploding population of feral rabbits in the surface area.

In the United kingdom, fresh rabbit is sold in butcher shops and markets, and some supermarkets sell frozen rabbit meat. At farmers markets at that place, including the famous Borough Market in London, rabbit carcasses are sometimes displayed hanging, unbutchered (in the traditional mode), next to braces of pheasant or other small game. Rabbit meat is a feature of Moroccan cuisine, where it is cooked in a tajine with "raisins and grilled almonds added a few minutes before serving".[66] In People's republic of china, rabbit meat is particularly popular in Sichuan cuisine, with its stewed rabbit, spicy diced rabbit, BBQ-style rabbit, and fifty-fifty spicy rabbit heads, which have been compared to spicy duck neck.[63] Rabbit meat is comparatively unpopular elsewhere in the Asia-Pacific.

An extremely rare infection associated with rabbits-as-nutrient is tularemia (also known every bit rabbit fever), which may be contracted from an infected rabbit.[67] Hunters are at college risk for tularemia because of the potential for inhaling the bacteria during the skinning procedure.

In addition to their meat, rabbits are used for their wool, fur, and pelts, too every bit their nitrogen-rich manure and their high-protein milk.[68] Product industries accept developed domesticated rabbit breeds (such as the well-known Angora rabbit) to efficiently make full these needs.

In art, literature, and civilization

Rabbits are ofttimes used as a symbol of fertility or rebirth, and have long been associated with spring and Easter as the Easter Bunny. The species' office as a prey animal with few defenses evokes vulnerability and innocence, and in folklore and modern children'south stories, rabbits often appear every bit sympathetic characters, able to connect easily with youth of all kinds (for case, the Velveteen Rabbit, or Thumper in Bambi).

With its reputation as a prolific breeder, the rabbit juxtaposes sexuality with innocence, as in the Playboy Bunny. The rabbit (as a swift casualty animal) is as well known for its speed, agility, and endurance, symbolized (for example) by the marketing icons the Analeptic Bunny and the Duracell Bunny.

Folklore

The rabbit ofttimes appears in folklore as the trickster archetype, every bit he uses his cunning to outwit his enemies.

"Rabbit fools Elephant by showing the reflection of the moon".

Illustration (from 1354) of the Panchatantra

- In Aztec mythology, a pantheon of 4 hundred rabbit gods known as Centzon Totochtin, led by Ometochtli or Ii Rabbit, represented fertility, parties, and drunkenness.

- In Central Africa, the mutual hare (Kalulu), is "inevitably described" as a trickster figure.[69]

- In Chinese folklore, rabbits accompany Chang'e on the Moon. In the Chinese New year, the zodiacal rabbit is one of the twelve celestial animals in the Chinese zodiac. Note that the Vietnamese zodiac includes a zodiacal cat in identify of the rabbit, possibly because rabbits did not inhabit Vietnam.[ citation needed ] The nigh common explanation, notwithstanding, is that the ancient Vietnamese give-and-take for "rabbit" (mao) sounds similar the Chinese word for "cat" (卯, mao).[seventy]

- In Japanese tradition, rabbits alive on the Moon where they brand mochi, the popular snack of mashed sticky rice. This comes from interpreting the blueprint of dark patches on the moon every bit a rabbit standing on tiptoes on the left pounding on an usu, a Japanese mortar.

- In Jewish folklore, rabbits (shfanim שפנים) are associated with cowardice, a usage withal current in gimmicky Israeli spoken Hebrew (similar to the English colloquial employ of "chicken" to denote cowardice).

- In Korean mythology, as in Japanese, rabbits alive on the moon making rice cakes ("Tteok" in Korean).

- In Anishinaabe traditional behavior, held by the Ojibwe and another Native American peoples, Nanabozho, or Great Rabbit, is an important deity related to the creation of the globe.

- A Vietnamese mythological story portrays the rabbit of innocence and youthfulness. The Gods of the myth are shown to be hunting and killing rabbits to prove off their power.

- Buddhism, Christianity, and Judaism have associations with an ancient circular motif called the three rabbits (or "three hares"). Its pregnant ranges from "peace and tranquility", to purity or the Holy Trinity, to Kabbalistic levels of the soul or to the Jewish diaspora. The tripartite symbol also appears in heraldry and even tattoos.

The rabbit as trickster is a part of American popular civilisation, equally Br'er Rabbit (from African-American folktales and, later, Disney blitheness) and Bugs Bunny (the cartoon grapheme from Warner Bros.), for example.

Anthropomorphized rabbits have appeared in film and literature, in Alice'southward Adventures in Wonderland (the White Rabbit and the March Hare characters), in Watership Down (including the moving-picture show and television adaptations), in Rabbit Hill (past Robert Lawson), and in the Peter Rabbit stories (past Beatrix Potter). In the 1920s, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, was a popular drawing grapheme.

WWII USAF pilot D. R. Emerson

"flys with a rabbit's foot talisman,

a gift from a New York girl friend"

A rabbit'south foot may exist carried as an amulet, believed to bring protection and skillful luck. This belief is constitute in many parts of the earth, with the earliest use existence recorded in Europe c. 600 BC.[71]

On the Isle of Portland in Dorset, UK, the rabbit is said to be unlucky and even speaking the beast'due south name tin can crusade upset amongst older island residents. This is thought to date back to early times in the local quarrying manufacture where (to save space) extracted stones that were not fit for sale were set aside in what became tall, unstable walls. The local rabbits' tendency to burrow in that location would weaken the walls and their collapse resulted in injuries or fifty-fifty death. Thus, invoking the proper name of the culprit became an unlucky act to be avoided. In the local civilization to this 24-hour interval, the rabbit (when he has to be referred to) may instead be called a "long ears" or "surreptitious mutton", so as not to risk bringing a downfall upon oneself. While it was truthful 50 years ago[ when? ] that a pub on the island could be emptied by calling out the discussion "rabbit", this has become more than fable than fact in modern times.[ citation needed ]

In other parts of Uk and in North America, invoking the rabbit's proper noun may instead bring good luck. "Rabbit rabbit rabbit" is ane variant of an apotropaic or talismanic superstition that involves saying or repeating the word "rabbit" (or "rabbits" or "white rabbits" or some combination thereof) out loud upon waking on the outset 24-hour interval of each month, considering doing and so will ensure good fortune for the duration of that month.

The "rabbit test" is a term, first used in 1949, for the Friedman test, an early on diagnostic tool for detecting a pregnancy in humans. It is a common misconception (or perhaps an urban legend) that the test-rabbit would die if the woman was pregnant. This led to the phrase "the rabbit died" condign a euphemism for a positive pregnancy test.

See besides

- Animal rail

- Cuniculture

- Dwarf rabbit

- Hare games

- Jackalope

- List of beast names

- List of rabbit breeds

- Lop rabbit

- Rabbits in the arts

- Rabbit bear witness jumping

References

Notes

- ^ This genus is considered a hare, not a rabbit

Citations

- ^ "Information export". DAD-IS (Domestic Animal Multifariousness Data System). FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). 21 November 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- ^ "coney". Online Etymology Dictionary . Retrieved ii March 2018.

- ^ "The Collective Substantive Page". Archived from the original on i February 2008. Retrieved 30 January 2008.

- ^ McClure, DVM PhD DACLAM, Diane (2018). "Breeding and Reproduction of Rabbits". Merck Veterinarian Transmission. Archived from the original on half dozen January 2018. Retrieved 5 Jan 2018.

- ^ "Common Questions: What Do You lot Call a Grouping of...?". archived copy of Fauna Congregations, or What Do You Phone call a Group of.....?. U.S. Geological Survey Northern Prairie Wildlife Inquiry Center. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ "rabbit". Online Etymology Dictionary . Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ Brown, Louise (2001). How to Care for Your Rabbit. Kingdom Books. p. six. ISBN978-1-85279-167-iv.

- ^ Katherine Quesenberry & James W. Carpenter, Ferrets, Rabbits, and Rodents: Clinical Medicine and Surgery (tertiary ed. 2011).

- ^ d'Ovidio, Dario; Pierantoni, Ludovica; Noviello, Emilio; Pirrone, Federica (September 2016). "Sex differences in man-directed social beliefs in pet rabbits". Periodical of Veterinarian Beliefs. fifteen: 37–42. doi:x.1016/j.jveb.2016.08.072.

- ^ van Praag, Esther (2005). "Deformed claws in a rabbit, after traumatic fractures" (PDF). MediRabbit.

- ^ a b c "rabbit". Encyclopædia Britannica (Standard ed.). Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2007.

- ^ "What practice Rabbits Run into?". Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ^ Bensley, Benjamin Arthur (1910). Practical anatomy of the rabbit. The Academy Printing. p. i.

rabbit skeletal anatomy.

- ^ "Description and Physical Characteristics of Rabbits - All Other Pets - Merck Veterinary Manual". Merck Veterinarian Manual . Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ D.A.B.V.P., Margaret A. Wissman, D.V.M. "Rabbit Anatomy". exoticpetvet.net . Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ Susan., Lumpkin (2011). Rabbits : the creature answer guide. Seidensticker, John. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN9781421401263. OCLC 794700391.

- ^ Geiser, Max; Trueta, Joseph (May 1958). "Muscle action, os rarefaction and os germination". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume. 40-B (two): 282–311. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.40B2.282. PMID 13539115.

- ^ Lieber, Richard L.; Blevins, Field T. (January 1989). "Skeletal musculus architecture of the rabbit hindlimb: Functional implications of muscle design". Journal of Morphology. 199 (one): 93–101. doi:10.1002/jmor.1051990108. PMID 2921772. S2CID 25344889.

- ^ Hall, E. Raymond (2001). The Mammals of North America. The Blackburn Press. ISBN978-1930665354.

- ^ Bensley, Benjamin Arthur (1910). Practical anatomy of the rabbit. The Academy Press.

- ^ Meyer, D. L. (1971). "Single Unit of measurement Responses of Rabbit Ear-Muscles to Postural and Accelerative Stimulation". Experimental Brain Research. 14 (2): 118–26. doi:ten.1007/BF00234795. PMID 5016586. S2CID 6466476.

- ^ Capello, Vittorio (2006). "Lateral Ear Canal Resection and Ablation in Pet Rabbits" (PDF). The N American Veterinarian Conference. xx: 1711–1713.

- ^ Vella, David (2012). Ferrets, Rabbits, and Rodents: Clinical Medicine and Surgery. Elsevier. ISBN978-1-4160-6621-7.

- ^ a b c Parsons, Paige M. (2018). "Rabbit Ears: A Structural Look: ...injury or affliction, can ship your rabbit into a spin". House Rabbit Society.

- ^ Romanovsky, A. A. (March 2014). "Skin temperature: its role in thermoregulation". Acta Physiologica. 210 (three): 498–507. doi:10.1111/apha.12231. PMC4159593. PMID 24716231.

- ^ Vella, David (2012). Ferrets, Rabbits, and Rodents: Clinical, Medicine, and Surgery. Elsevier. ISBN9781416066217. [ page needed ]

- ^ Fayez, I; Marai, K; Alnaimy, A; Habeeb, M (1994). "Thermoregulation in rabbits". In Baselga, Yard; Marai, I.F.M. (eds.). Rabbit production in hot climates. Zaragoza: CIHEAM. pp. 33–41.

- ^ a b c d east Johnson-Delaney, Cathy A.; Orosz, Susan E. (2011). "Rabbit Respiratory Organization: Clinical Anatomy, Physiology and Disease". Veterinary Clinics of North America: Exotic Animal Practice. 14 (2): 257–266. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2011.03.002. PMID 21601814.

- ^ a b c d Smith, David G. (2019). A dissection guide & atlas to the rabbit. ISBN978-1617319372. OCLC 1084742187.

- ^ a b c Jekl, Vladimi (2012). "Arroyo to Rabbit Respiratory Disease". WSAVA/FECAVA/BSAVA World Congress.

Every bit obligate nasal breathers, rabbits with upper airway disease will attempt to exhale through their mouths, which prevents feeding and drinking and could be rapidly fatal.

- ^ a b Autifi, Mohamed Abdul Haye; El-Banna, Ahmed Kamal; Ebaid, Ashraf El- Sayed (2015). "Morphological Study of Rabbit Lung, Bronchial Tree, and Pulmonary Vessels Using Corrosion Cast Technique". Al-Azhar Assiut Medical Journal. 13 (three): 41–51.

- ^ "Rabbits: The Mystery of Poop". bio.miami.edu . Retrieved three December 2018.

- ^ "Data for Rabbit Owners — Oak Tree Veterinary Centre". Oaktreevet.co.uk. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "Feeding the Pet Rabbit"

- ^ Dr. Byron de la Navarre's "Care of Rabbits" Susan A. Brown, DVM's "Overview of Mutual Rabbit Diseases: Diseases Related to Nutrition"

- ^ The Private Life of the Rabbit, R. Yard. Lockley, 1964. Chapter x.

- ^ Bernard East. Rollin (13 March 1995). The Experimental Animal in Biomedical Research: Care, Husbandry, and Well-Being-An Overview by Species, Volume 2. CRC Press. p. 359. ISBN9780849349829.

- ^ Karr-Lilienthal, Phd (University of Nebraska - Lincoln), Lisa (4 November 2011). "The Digestive System of the Rabbit". eXtension (a Part of the Cooperative Extension Service). Archived from the original on vi January 2018. Retrieved 5 Jan 2018.

- ^ "Living with a Business firm Rabbit". Archived from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d Foote, Robert H; Carney, Edward W (2000). "The rabbit as a model for reproductive and developmental toxicity studies". Reproductive Toxicology. 14 (six): 477–493. doi:10.1016/s0890-6238(00)00101-5. ISSN 0890-6238. PMID 11099874.

- ^ a b c d e "Rabbit Reproduction Basics". LafeberVet. 5 May 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ Weisbroth, Steven H.; Flatt, Ronald E.; Kraus, Alan L. (1974). The Biology of the Laboratory Rabbit. doi:x.1016/c2013-0-11681-9. ISBN9780127421506.

- ^ "Understanding the Mating Process for Convenance Rabbits". florida4h.org . Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ^ Jilge, B (1991). "The rabbit: a diurnal or a nocturnal fauna?". Journal of Experimental Creature Science. 34 (5–six): 170–183. PMID 1814463.

- ^ "twoscore Winks?" Jennifer South. Holland, National Geographic Vol. 220, No. 1. July 2011.

- ^ Wright, Samantha (2011). For The Dearest of Parsley. A Guide To Your Rabbit's Most Common Behaviours. Lulu. pp. 35–36. ISBN978-ane-4467-9111-0.

- ^ Cooke, Brian Douglas (2014). Australia's War Against Rabbits. CSIRO Publishing. ISBN978-0-643-09612-seven. Archived from the original on 7 June 2014.

- ^ Woods, Maggie. "Parasites of Rabbits". Chicago Exotics, PC. Archived from the original on ii March 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ^ Boschert, Ken. "Internal Parasites of Rabbits". Net Vet. Archived from the original on two April 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ^ Krempels, Dana. "GastroIntestinal Stasis, The Silent Killer". Section of Biology at the University of Miami. Archived from the original on 19 June 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ "Rabies: Other Wild fauna". Centers for Illness Command and Prevention. 15 November 2011. Archived from the original on 20 December 2010. Retrieved twenty December 2012.

- ^ Fedriani, J. M.; Palomares, F.; Delibes, M. (1999). "Niche relations among three sympatric Mediterranean carnivores" (PDF). Oecologia. 121 (one): 138–148. Bibcode:1999Oecol.121..138F. CiteSeerX10.one.1.587.7215. doi:x.1007/s004420050915. JSTOR 4222449. PMID 28307883. S2CID 39202154. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ Tynes, Valarie V. Behavior of Exotic Pets Archived 6 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Wiley Blackwell, 2010, p. lxx.

- ^ Davis, Susan E. and DeMello, Margo Stories Rabbits Tell: A Natural And Cultural History of A Misunderstood Creature Archived 6 May 2016 at the Wayback Auto. Lantern Books, 2003, p. 27.

- ^ Glenday, Craig (2013). Guinness Globe Records 2014. pp. 043. ISBN978-1-908843-15-ix.

- ^ Cottontail rabbit at Indiana Department of Natural Resources Archived 17 November 2016 at the Wayback Auto

- ^ a b c "Rabbit Habitats". Archived from the original on 4 August 2009. Retrieved vii July 2009.

- ^ Beischer, DE; Fregly, AR (1962). "Animals and human being in space. A chronology and annotated bibliography through the twelvemonth 1960". US Naval School of Aviation Medicine. ONR TR ACR-64 (AD0272581). Archived from the original on 11 August 2015. Retrieved fourteen June 2011.

- ^ Department of Primary Industries and Regional Evolution; Agriculture and Food Division; Pest and Affliction Data Service (PaDIS). "Rabbit control: fumigation". agric.wa.gov.au. Government of Western Australia. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ^ "Feral animals in Australia — Invasive species". Surround.gov.au. 1 Feb 2010. Archived from the original on 21 July 2010. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ^ "Rabbits — The part of government — Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Teara.govt.nz. i March 2009. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011. Retrieved thirty August 2010.

- ^ "Rabbit: From Farm to Table". Archived from the original on v July 2008.

- ^ a b Olivia Geng, French Rabbit Heads: The Newest Delicacy in Chinese Cuisine Archived 14 July 2017 at the Wayback Car. The Wall Street Periodical Blog, 13 June 2014

- ^ "FAOSTAT". FAO . Retrieved 25 Oct 2019.

- ^ FAO - The Rabbit - Husbandry, health and product. Archived 23 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 'Traditional Moroccan Cooking, Recipes from Fez', by Madame Guinadeau. (Serif, London, 2003). ISBN 1-897959-43-v.

- ^ "Tularemia (Rabbit fever)". Health.utah.gov. xvi June 2003. Archived from the original on 26 May 2010. Retrieved thirty August 2010.

- ^ Houdebine, Louis-Marie; Fan, Jianglin (1 June 2009). Rabbit Biotechnology: Rabbit Genomics, Transgenesis, Cloning and Models. シュプリンガー・ジャパン株式会社. pp. 68–72. ISBN978-xc-481-2226-4. Archived from the original on 26 Apr 2014. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ Brian Morris, The Power of Animals: An Ethnography, p. 177 (2000).

- ^ "Twelvemonth of the Cat OR Yr of the Rabbit?". nwasianweekly.com. three Feb 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ Ellis, Bill (1 January 2004). Friction match Ascending: The Occult in Folklore and Pop Culture. Academy Press of Kentucky. ISBN978-0813122892.

Further reading

- Windling, Terri. The Symbolism of Rabbits and Hares [usurped!]

External links

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rabbits. |

| | Wikiquote has quotations related to: Rabbit |

- American Rabbit Breeders Clan organization, which promotes all phases of rabbit keeping

- Business firm Rabbit Society an activist organisation that promotes keeping rabbits indoors

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rabbit

0 Response to "What Is a Litter of Baby Rabbits Called"

Enregistrer un commentaire